When the Rule of Law and Accountability Advocacy Centre (RULAAC), the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA), and a coalition of Southeast civil society organizations convened the Peace and Security Stakeholders’ Summit in Enugu in February 2025, the discussions were frank, evidence-based, and forward-looking.

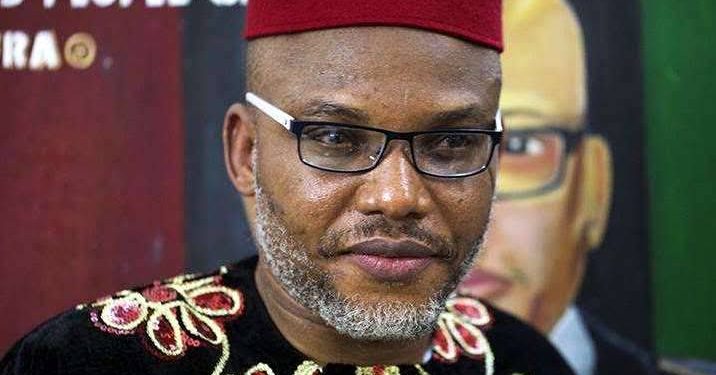

Participants critically examined the intersections of security, human rights, civic space, and development in the beleaguered Southeast. One of the most resonant recommendations that emerged was clear: the release of Nnamdi Kanu is essential to reconciliation, reduction of violence, and the pursuit of lasting peace in the region.

The Roots of Agitation

The separatist agitation in the Southeast did not begin with Nnamdi Kanu or the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB). It is rooted in decades of political and economic exclusion, neglect, and feelings of injustice experienced by the people of the region.

The end of the Nigeria–Biafra civil war was expected to usher in the Three Rs – Reconciliation, Reconstruction, and Rehabilitation. Instead, what followed was marginalization, the destruction of civic trust, and a widening gap between the Southeast and the Nigerian state.

IPOB’s agitation, led by Nnamdi Kanu, represents a political expression of these long-festering grievances. And because it is political, it demands a political solution, not a militarized or punitive one.

Justice, Double Standards, and Selective Treatment

Over the years, courts in Nigeria and in Kenya have ruled that Nnamdi Kanu’s extraordinary rendition was unlawful and violated both his personal rights and international law. Nigerian courts have also ordered his release. Yet, the Federal Government has refused to comply.

Contrast this with how other forms of armed agitation and violence have been handled.

Leaders of militant groups in the Niger Delta were granted amnesty and rewarded with contracts, employment, and scholarships abroad.

Sunday Igboho, who championed the Yoruba self-determination cause, was released.

The Federal Government has held open negotiations with so-called “repentant” bandits – many of whom have killed, kidnapped, and destroyed communities – even allowing them to attend peace meetings heavily armed and dictating terms. Thousands of Boko Haram members have been granted amnesty, rehabilitated, and in some cases, integrated into security agencies.

How, then, can Nnamdi Kanu be treated differently – as if, even if guilty of any offence, he poses a greater threat to national security than those who have waged terror against the state?

This glaring inconsistency raises a painful question: Is this yet another manifestation of the discriminatory treatment of the Southeast, reminiscent of former President Buhari’s remark about “treating them in the language they understand”?

A Repressive Approach That Fuels Insecurity

The worsening insecurity in the Southeast is largely a consequence of the federal and state governments’ repressive and heavy-handed responses to what began as peaceful agitation for inclusion and justice. By reducing every expression of dissent in the region to IPOB and criminalizing legitimate political grievances, the government has ignored a multiplicity of other drivers of insecurity – including political thuggery, cult violence, unemployment, economic collapse, and the erosion of public trust.

The militarization of civic spaces, arbitrary arrests, torture, and extrajudicial killings by security forces have only deepened alienation and hardened extremism. Every bullet fired in repression breeds a dozen more angry and alienated youths.

Beyond Kanu: The Cost of Continued Incarceration

Those calling for Nnamdi Kanu’s release are not doing so out of blind loyalty or endorsement of his rhetoric. They are calling for common sense and justice. His continued incarceration – despite multiple court orders and appeals from well-meaning Nigerians, political leaders, and traditional rulers – has become both a legal and moral scandal.

In the face of the government’s open negotiations with terrorists and violent criminals, the refusal to release Kanu reinforces the perception that the Southeast is treated under a different set of laws and standards. This sense of injustice continues to fuel anger, resentment, and insecurity.

The Path Forward

The Federal Government must demonstrate a genuine commitment to peace and national healing by complying with court orders and releasing Nnamdi Kanu. His release would not only open the door to dialogue and reconciliation but also remove one of the key rallying points exploited by violent elements in the region.

History has shown that coercion does not resolve political conflicts – dialogue does. The amnesty programme in the Niger Delta, flawed as it was, proved that engagement and inclusion can end violence where force failed. The same approach is needed in the Southeast today.

A sincere political solution that addresses the root causes of exclusion and injustice – alongside accountability for human rights violations – is the only sustainable way to restore peace and rebuild trust between the government and the people.

In the final analysis, the continued detention of Nnamdi Kanu is unjust, unlawful, and counterproductive. It perpetuates a cycle of alienation and distrust that fuels the insecurity now ravaging the Southeast.

Nigeria cannot claim to be a democracy governed by the rule of law while it chooses which court orders to obey and which region deserves justice.

Releasing Nnamdi Kanu is not a concession – it is a necessary step toward restoring justice, rebuilding peace, and reaffirming that all Nigerians, regardless of region, are equal before the law.

Okechukwu Nwanguma

Executive Director, Rule of Law and Accountability Advocacy Centre (RULAAC)