Who is deceiving who? In today’s Nigeria, terrorists and bandits who have killed soldiers and razed communities are being released, pardoned, and even absorbed into the Nigerian Army under government-sponsored deradicalization programs. Yet, Mazi Nnamdi Kanu, leader of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), languishes in detention despite deteriorating health. This hypocrisy exposes a deep wound in the Nigerian state one that continues to remind the Igbo that they are not treated as equal citizens.

The Nigerian Civil War, popularly known as the Biafra War, claimed over three million lives from the Igbo side. Decades later, the scars remain raw. Every policy of exclusion, every act of discrimination, and every reminder of second-class treatment reopens that wound. The resilience of Ndigbo, however, remains unmatched. It is akin to a hunter venturing into a forest filled with deadly beasts, armed with nothing but his bare hands, yet returning with a bountiful catch undaunted, uncomplaining, and unbroken.

Today, Nnamdi Kanu’s lawyers have revealed his health crisis: dangerously low potassium levels and complications that could trigger heart failure. A letter signed by his Special Counsel, Barrister Aloy Ejimakor, and addressed to the Director-General of the Department of State Services (DSS) on September 23, 2025, urgently requested hospital admission for Kanu at Clover Hospital, Abuja, under the care of Dr. Michael Eze. The urgency was such that the hospital scheduled to receive him immediately.

Yet, the Nigerian state continues to play politics. Justice Musa Liman of the Federal High Court declined to hear a motion seeking Kanu’s transfer to the National Hospital, citing lack of jurisdiction as his vacation fiat had expired. Instead, the case was pushed back into bureaucratic limbo, while Kanu’s health deteriorates in DSS custody.

Contrast this with how terrorists and bandits are treated. Under Operation Safe Corridor (OPSC), repentant Boko Haram members are offered deradicalization, vocational training, and reintegration into society. This program mirrors the earlier Niger Delta Amnesty Programme, where militants received incentives and training. Despite widespread criticism that such initiatives embolden impunity, they are still applied yet consistently denied to the Southeast and to Kanu.

Even more shocking is the record of killings: over 10,217 people murdered since the current administration took office, including 6,896 in Benue and 2,630 in Plateau. In Zamfara alone, 638 villages have been sacked by bandits. Still, these killers are given amnesty, pardons, and in some cases, platforms for press interviews. Meanwhile, the federal government ignores pleas from Ndigbo leaders, civil society, and international voices calling for Kanu’s release.

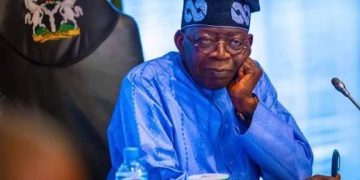

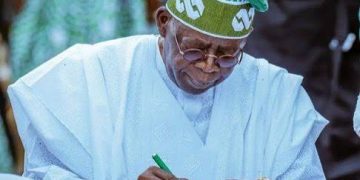

Nigeria’s Democracy Day of June 12 offers a stark lesson. President Bola Ahmed Tinubu pardoned the “Ogoni Nine,” including Ken Saro-Wiwa, decades after their execution for resisting Shell’s environmental devastation in the Niger Delta. While commendable, it was a correction made too late. Will history repeat itself with Nnamdi Kanu? Must the government wait for irreversible damage before acting?

The injustice against Ndigbo is neither subtle nor hidden. Since the civil war, inclusion in governance has been tokenistic at best. Federal appointments, security structures, and national policies reflect systemic exclusion. The treatment of Nnamdi Kanu, even in a health crisis, reinforces the message: the Igbo are still not seen as equal Nigerians.

This is not merely about one man. It is about the dignity of a people. If terrorists who shed innocent blood are deserving of pardon and reintegration, then why is an agitator, whose primary weapon has been rhetoric, denied even medical attention? Why is he a threat to two successive administrations?

President Tinubu has a historic opportunity. By ordering Kanu’s release, he can write his name in history as a unifier who corrected decades of injustice. Failure to do so will not only deepen Igbo disenchantment but will also expose, yet again, the double standards that fuel Nigeria’s disunity.

For Ndigbo, the story remains the same since 1970: injustice, exclusion, and betrayal. And every day Kanu remains in detention while bandits are set free, the question grows louder why can’t the Igbo be treated as equal in Nigeria?

Daniel Okonkwo is a seasoned writer, human rights advocate, and public affairs analyst, renowned for his thought-provoking articles on governance, justice, and social equity. Through his platform, Profiles International Human Rights Advocate, he consistently sheds light on pressing issues affecting Nigeria and beyond, amplifying voices that call for accountability and reform. He is also a professional transcriptionist and experienced petition writer, with over 1,000 published articles to his credit on Google. Many of his works have been featured in Sahara Reporters and other major news outlets. In addition, he works as a ghostwriter, freelancer, and journalist.