Is Wole Soyinka genuinely aggrieved about the size of the First Son’s security detail, or did the situation bruise his ego because, for once, he felt subjected to the same inconveniences ordinary Nigerians face? Is he truly concerned about public welfare, or is this a performance aimed at reinforcing his moral authority? And why speak out now? His claim that he contacted the National Security Adviser from France appears somewhat boastful. As an educator and elder statesman, there is little need to publicly announce such interactions. Why not approach Seyi Tinubu privately? Why escalate the matter to the NSA, especially given his personal closeness to the First Family? The public outburst, to many, appears theatrical a dramatic performance staged for maximum effect.

Nigeria’s ongoing security challenges, ranging from terrorism and banditry to kidnappings and rural attacks, have intensified scrutiny of how limited security resources are allocated. This scrutiny resurfaced sharply following Soyinka’s recent remarks questioning the size of the security convoy assigned to Seyi Tinubu, son of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu.

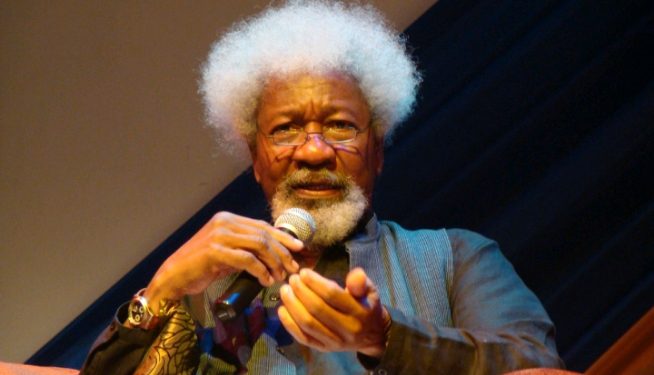

Speaking at the 20th Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism Awards in Lagos, the Nobel Laureate recounted his shock at what he described as an “extravagant display” of state-provided protection. He jokingly remarked that if an insurgency were to erupt, “perhaps the President should ask Seyi to go and handle it,” given the size of his escort. Yet behind the humour, Soyinka insisted, lay “a serious matter of priority and fairness.”

His comments reflect frustration with perceived excessive privilege at a time of widespread insecurity. However, the critique disregards the practical and necessary security protocols associated with members of the First Family, consistent with global standards and grounded in real threats.

The president’s immediate family is typically classified as high-value individuals (HVIs) due to the strategic risks associated with their status. In a security environment like Nigeria’s, marked by insurgency, political hostility, and targeted kidnapping, the need for comprehensive protection is neither unusual nor optional.

As the son of a sitting president, Seyi Tinubu is particularly vulnerable to risks of abduction, intimidation, and political attacks. His security detail, usually comprising an Aide-de-Camp (ADC), officers from the Nigeria Police Force and the DSS, and bulletproof vehicles, is part of standard procedures for safeguarding the First Family. These measures are not extraordinary privileges; they are essential defensive strategies designed to protect the first son’s stability by ensuring the safety of individuals connected to the presidency.

In many democracies, including the United States, France, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, the children of presidents and prime ministers receive state-funded security, regardless of age or public engagement. Nigeria’s approach is consistent with these global practices.

While the need to secure the First Family is widely acknowledged, Soyinka’s argument focuses on scale rather than legitimacy. He contends that dedicating what he perceives as an excessive number of operatives to a single individual reflects misaligned national priorities. “Concentrating a battalion of operatives around one person,” he warned, “is inconsistent with the realities of a nation battling kidnappings, rural attacks, insurgency, and criminal violence.”

He recounted a recent incident at a hotel in Ikoyi that left him “astonished” by the size of Seyi Tinubu’s convoy. Confused, he said, he contacted the National Security Adviser for clarification: “I’ve just seen something I can’t believe. Do you mean that a child of the head of state goes around with an army for his protection?”

Despite his dramatic storytelling, Soyinka raises a valid question: At what point does necessary protection become excessive, especially in the context of national insecurity?

However, his remarks appear to many less like a constructive critique and more like a personalized attack on an individual who neither designed nor controls the security architecture assigned to him. The insinuation that Seyi Tinubu is unworthy of such protection or lacks the maturity to merit it has been viewed as intellectually inconsistent coming from a Nobel laureate.

There is a growing sentiment that even the most brilliant minds can be clouded by bias, leading to sweeping judgments that overlook critical context. In this case, Soyinka’s comments appear to personalize a systemic issue, shifting attention away from institutional shortcomings and directing it unfairly at one individual.

Protection for the First Family is not a discretionary privilege; it is a State obligation informed by intelligence assessments, established precedent, and security risk calculations.

Nigeria’s security institutions are undeniably overstretched. Millions of citizens face daily threats while security forces combat insurgency, banditry, and violent crime. Soyinka’s central assertion that national security resources must reflect national priorities remains valid and worthy of discussion.

But such discussions must be rational, contextually grounded, and free of personalized attacks. The goal should be to address systemic weaknesses without turning legitimate protective measures into subjects of ridicule or resentment.

Ultimately, this debate highlights a deeper national dilemma: How can Nigeria protect its leaders and their families without appearing to neglect the security needs of ordinary citizens? Achieving balance, transparency, and fairness is essential.

Soyinka’s remarks, however, veer into territory that many consider unfair. An unfair remark is biased, unjustified, or disproportionate to the actual circumstances. It may exaggerate minor details or distort context in ways that cause harm to a person’s reputation and such statements can, in certain situations, verge on the defamatory. They may also create a misleading public perception, subjecting the target to unwarranted criticism or hostility. In this case, the criticism directed at Seyi Tinubu appears excessive relative to the situation and fails to conform to accepted standards of fairness or honesty.

Daniel Nduka Okonkwo is a seasoned writer, human rights advocate, and public affairs analyst, widely recognized for his incisive commentary on governance, justice, and social equity. Through his platform, Profiles International Human Rights Advocate, he has consistently illuminated critical social and political issues in Nigeria and beyond, championing accountability, transparency, and reform. With a portfolio of more than 1,000 published articles available on Google, Okonkwo’s works have appeared in prominent outlets such as Sahara Reporters and other leading media platforms. Beyond journalism, he is an accomplished transcriptionist and experienced petition writer, known for his precision and persuasive communication. He also works as a ghostwriter and freelance journalist, contributing his expertise to diverse projects that promote truth, integrity, and the protection of human rights.