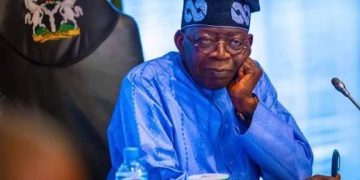

Some critics of Bola Tinubu assume the Nigerian president is perpetually adrift, travelling frequently, speaking elliptically, appearing physically unsteady at times, and projecting an air of distance from the daily anxieties of the public. To them, he looks distracted, disconnected, and drowning in a mountain of duty calls.

He is not.

While Buhari was aloof, Tinubu was curled up on the rooftop, cunningly pulling the strings like a village Kabiyesi. His appearance of confusion is not evidence of the absence of mind. It is part of the method. Tinubu’s political strength has long been his ability to operate behind a curtain of ambiguity. What looks like drift is often by design. What appears to be disorder frequently conceals direction.

A liquid stain on his pants upon getting up, or a fall on the parade ground after a misstep, triggers dusk and noise that obscure the undertaker’s mission already in progress.

Those who benefit from what matters to him see strategic brilliance in which they are well pleased. Those who do not factor in the scale of things see incompetence. But actual decisions happen somewhere else. Power shifts and institutional and resource control occur while the public focuses on artificial optics.

Things you do not see are more important than the things you see.

Critics of Donald Trump experience a different version of the same misreading. Trump appears impulsive, theatrical, and incapable of restraint. His politics feel like a continuous spectacle, a rolling storm of 3.00 am Truth Social posts, controversies out of every press conference, and crises manufactured to manipulate the news cycle.

Spectacle, like obscurity, can serve the same purpose.

Donald Trump and Bola Tinubu practice different styles of the same political misdirection. Tinubu prefers opacity on things as basic as his ordinary biographical facts, while Trump chooses information overload. In matters big or small, Tinubu lowers the volume of his reaction until scrutiny fades, while Trump raises it so high that scrutiny collapses from exhaustion and rupture of the eardrum. Tinubu hides in the fog, while Trump hides in the noise.

The effect, however, is strikingly similar: public debate orbits personality, performance, and daily drama, while bigger structural changes advance with less resistance. While one flings red meat to hungry crocodiles ready to muddy the pond, the other deploys hunger to instigate a fervent season of prayer, fasting, and speaking in tongues.

Tinubu’s first day in office brought the removal of fuel subsidies and the floating of the naira. He framed these decisions as necessary economic reforms to prevent national collapse. The immediate result was a sharp decline in purchasing power for ordinary Nigerians. Tinubu’s team emphasised sacrifice as a civic duty.

Yet the visible lifestyle of political power did not contract in parallel. Instead, they bought new jets, a yacht, limousines, and kitchenware. Each year, they invest billions to install solar panels on Aso Rock while the national grid collapses like Nasir el-Rufai’s alibi on the disappearance of Daditaya.

Meanwhile, the people charged with holding the executive branch to account went from brown envelopes stuffed with dollar bills to prayer tokens, and then to scrumptious meals at the First Lady’s home. The state moved toward expanded borrowing and additional tax measures, even as poverty deepened from the hinterlands to the slums and into what used to be the government-reserved areas.

The poor, they said, would be exempt from taxes, but merchants and service providers are free to pass their additional tax burdens onto the same poor folks. The dishonesty stinks to high heaven. These outcomes of their policies were obvious to them when Goodluck Jonathan was president, and they were in opposition. Then, they were prepared to carry placards on the streets to denounce these same outcomes.

Now in government, as they implement these draconian and drastic policies, they seem unprepared to deal with the devastation, as if it surprised them that prices were rising and people were getting poorer. After years of uncontrolled borrowing, the Minister of Finance is now troubled by a rising debt service burden.

Trump’s choreography operates in a different register but follows a related logic. Cycles of outrage and conflict dominate the field of attention. Supporters mobilise around former citizens now perceived as enemies of the state. In contrast, opponents mobilise around scandals, hoping to nitpick each item until they uncover the DNA of Donald Trump pulling the puppets’ strings.

While this is going on, he is reshaping institutions beyond recognition, stretching norms beyond the elastic limits, and concentrating economic advantages into fewer and fewer hands of new-age oligarchies determined to surpass John D. Rockefeller, Carnegie, and J. P. Morgan.

Both leaders rely on a simple political reality: citizens cannot effectively resist changes they are not clearly tracking. With deliberate resistance to releasing information, they intentionally leave citizens in the dark.

It happened with Nigeria’s doctored Tax Bill and the hurriedly passed Electoral Bill. Even blatant conflicts of interest look too small a concern when encampments for possible war are under construction. Misdirection, in the hands of master manipulators, does not require invisibility. It requires quiet or loud redirection of focus.

Like magicians, their ability to pull a rat out of an empty hat depends solely on their ability to distract. A stage magician does not fail because the trick is impossible. He succeeds because the audience is looking at the wrong hand. And that is the common denominator of the two leaders’ performances.

While you grumble that Tinubu conferred the Grand Commander of the Order of Nigeria (GCON) on his paddy, Gilbert Chagoury, foreign troops sneaked into Nigeria, and France took control of the backbone of Nigeria’s internal revenue.

While Trump’s detractors are busy demanding the release of the Epstein files, he is violating international and U.S. laws in his attacks on suspected drug boats in the Caribbean and Pacific seas. As the U.S. masses ponder Trump’s kidnapping of the president of Venezuela, exerting an economic chokehold on Cuba, constantly ratcheting up pressure on Iran with a genuine threat of repeated attacks, making a claim of Greenland, and even Canada, off-camera deals take place.

A recent New Yorker calculation put Trump’s additional wealth since returning to the White House at about $4 billion. Tinubu’s friend, Chagoury, made the Nigerian equivalent of that wealth jump from just one no-bid contract for a Lagos-Calabar coastal highway.

While Tinubu ignores Nyesom Wike’s impunity in Abuja, Rivers, and beyond as long as he ultimately positions him for reelection and repaints buildings and names them after him, Trump bared by term limit, will build an arch over DC road, a ballroom on the former White House Rose Garden, and hold hostage tunnel projects in New York and beyond, unless Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer, agrees to rename Pen Station and Dules airport in Washington DC after him.

While Trump has his Attorney General, Bondi, calling sitting U.S. Senators losers, in addition to what the White House Press Secretary spews from the podium every day, Tinubu has Bayo Onanuga, with special assistance from Reno Omokiri.

The progress they both promote is much shallower than it appears, while the damage is much more devastating than it seems. The cost of things advertised as inevitable reforms to avoid Nigeria’s imminent collapse is more damaging in the long run than the short-term pain acknowledged or the long-term gain promised.

While Nigeria’s National Assembly continues to rubber-stamp, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a challenge to Trump’s use of tariffs as a political tool, appears ready to put the brakes on the expansion of the president’s power beyond what the Constitution allows.

Trump, in effect, invites the audience to watch the performance in his now-famous end-of-social-media post: “Thank you for your attention to this matter.” Tinubu, on the other hand, behaves as though no performance is taking place at all. Even if he poops on the pulpit or bandits kidnap half of his citizens, he acts as if it is another routine fire.

That is the only difference.

One governs through engineered spectacle. The other governs through massaged vagueness. But in both cases, the most consequential “state capture” occurs while attention is elsewhere.

Though the seventy-something old men use chaos as strategy and strategy as chaos in interchangeable ways, the distinction is not between chaos and strategy. It is between two styles of control: one loud, one quiet. Both operate on the same principle: if the show consumes public debate, the substantial transformation can proceed largely undisturbed.

Rudolf Ogoo Okonkwo teaches Post-colonial African History, Diasporic African Literature, and African Folktales at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He is the author of “This American Life Sef.” His latest book is “A Kiss That Never Was.”