The change promised by the ruling party has instead brought pain, suffering, and unbearable hardship to Nigerians. For many citizens, the central question remains straightforward Will their votes truly determine their leaders? As the government refuses to listen to protests and the APC fails to deliver meaningful progress, fear continues to grow among the people. With the 2027 elections approaching, many worry that another victory for the party could bring even greater suffering. In the eyes of many Nigerians, this administration has made the previous one seem almost angelic by comparison.

The All Progressives Congress (APC) used “Change” as its campaign slogan when it sought power, with a primary focus on creating three million jobs annually to tackle poverty and reduce unemployment. The party pledged to combat insecurity and protect the sovereignty of the nation. It emphasized industrialization, manufacturing, and agriculture as pathways to economic growth, and promised a robust investment program to rehabilitate and expand national infrastructure. It also vowed to wage a strict fight against corruption.

When the All Progressives Congress (APC) came to power in 2015, it promised to transform Nigeria through job creation, improved security, and aggressive anti-corruption measures. Its agenda included massive infrastructure investment, economic reform, and a “Renewed Hope” for national development. However, despite these commitments, many Nigerians believe the party has fallen short of several of its initial expectations.

When Nigerians came out to exercise their rights as citizens and protest in defense of democratic principles, they sought a system capable of meeting international human rights standards. The right to protest is a fundamental democratic, legal, and human right that enables citizens to assemble peacefully, express grievances, and demand accountability.

This right is enshrined in Section 40 of the Nigerian Constitution and protected under international law. It guarantees freedom of expression and association, although it may be lawfully restricted in the interest of public safety, security, or the prevention of violence. The Court of Appeal has ruled that police permits are not required for peaceful rallies, emphasizing that the role of the police is to protect, not prevent, lawful assemblies.

However, while fundamental, the right to protest is not absolute. It must be exercised peacefully and may be subject to reasonable restrictions to maintain public order, safety, and health. These protections are also recognized under international instruments such as the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Yet questions remain about whether these rights are meaningful in practice when peaceful protesters demanding legitimate reforms are dispersed with tear gas.

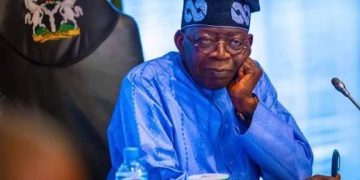

Even though the House of Representatives on Thursday apologized to protesters affected by the use of tear gas at the National Assembly earlier in the week, describing the incident as regrettable and promising a review of the circumstances, the incident has deepened public concern. The apology was delivered by House Spokesman Akin Rotimi at a press conference convened to address issues surrounding the Electoral Act recently signed into law by President Bola Ahmed Tinubu.

The newly signed electoral reform law has ignited widespread controversy, deepening tensions between the government, opposition parties, and civil society groups who warn that the legislation could undermine the credibility of future elections in Africa’s largest democracy.

Opposition figures described the reform as a “death warrant for credible elections,” while protest movements and electoral reform advocates argue that the law represents a missed opportunity to guarantee transparency ahead of the crucial 2027 general elections.

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu signed the Electoral Amendment Bill 2026 into law amid mounting debate over its provisions, particularly those governing the transmission and collation of election results.

The law introduces several reforms intended to improve Nigeria’s electoral process, including mandatory electronic transmission of results, legal recognition of the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS), and provisions requiring election funding to be released to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) at least one year before general elections.

However, a controversial clause allowing manual collation of results in areas where electronic transmission is deemed impossible has become the focal point of criticism.

Electoral democracy is defined by the principle that citizens exercise sovereignty through free, fair, and regular elections conducted under universal and equal suffrage. The legitimacy of government authority depends on transparent voting systems free from coercion, bribery, or manipulation.

Critics argue that allowing manual collation introduces vulnerabilities that could be exploited.

“The provision for manual transmission under the excuse of network failure creates a loophole that could undermine the integrity of the entire process,” said a civil society advocate involved in electoral reform campaigns.

Although the National Assembly approved electronic transmission, lawmakers retained exceptions for areas without reliable internet connectivity, a justification reform advocates say is increasingly difficult to defend in an era of expanding telecommunications coverage.

Civil society organizations warn that without compulsory real-time electronic transmission, opportunities for result manipulation may persist.

Opposition parties, including the African Democratic Congress (ADC), have openly condemned the law, arguing that credible elections are fundamental to Nigeria’s democratic legitimacy and stability.

Former presidential candidate Peter Obi, political economist Pat Utomi, and other prominent reform advocates have joined calls for stronger electoral safeguards and full transparency.

The absence of compulsory real-time electronic transmission

Allegations that the bill was passed without sufficient stakeholder consultation

Provisions imposing a ₦50 million party registration fee, which critics say could exclude grassroots political movements

Changes to voter identification requirements that may disenfranchise certain groups

For many reform advocates, the stakes extend beyond technical procedures to the very survival of democratic accountability.

When electoral processes are compromised, illegitimate leaders emerge, which leads to poor governance, corruption, and underdevelopment.

Public anger spilled into the streets of Abuja when demonstrators gathered at the National Assembly under the banner #OccupyNASS to demand mandatory electronic transmission of election results.

Security forces dispersed peaceful protesters with tear gas, escalating tensions and drawing condemnation from rights groups.

The rally included prominent activists such as former Minister of Education Oby Ezekwesili, activist and former presidential candidate Omoyele Sowore, and former Social Democratic Party presidential candidate Adewole Adebayo.

Protesters argued that real-time electronic transmission is essential to prevent vote manipulation and restore public trust in elections.

Electoral malpractice, including vote-buying, ballot stuffing, and election-related violence, has long been identified as a major obstacle to democratic consolidation and economic development across Africa.

Fraudulent elections weaken accountability, encourage corruption, and erode public trust in public institutions.

In Nigeria, repeated disputes over election credibility have fueled protests, legal battles, and political polarization.

While electoral protests can serve as catalysts for reform, they can also deepen instability if governments respond with repression rather than dialogue.

Amid the controversy, President Tinubu made a conciliatory appeal to Nigerians as Muslims began observing Ramadan, asking citizens to forgive him “if I have sinned.”

Although the statement was not directly linked to the electoral law, it was widely interpreted as an attempt to calm public tensions during a period of growing political uncertainty.

As Nigeria prepares for its next general elections, the debate over electoral reform highlights deeper questions about democratic legitimacy and governance.

While the government maintains that the new law strengthens the electoral framework, critics argue that its weaknesses could undermine public confidence.

The answer may define not only the credibility of Nigeria’s next election, but also the future of its democracy.

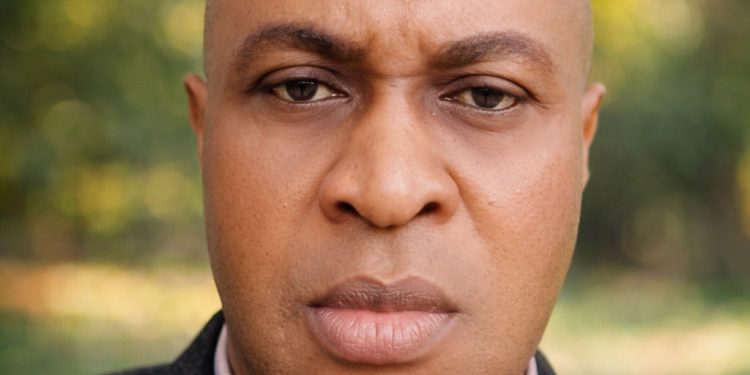

Daniel Nduka Okonkwo is a Nigerian investigative journalist, publisher of Profiles International Human Rights Advocate, and policy analyst whose work focuses on governance, institutional accountability, and political power. He is also a human rights activist, human rights advocate, and human rights journalist. His reporting and analysis have appeared in Sahara Reporters, African Defence Forum, Daily Intel Newspapers, Opinion Nigeria, African Angle, and other international media platforms. He writes from Nigeria and can be reached at dan.okonkwo.73@gmail.com.