Who will deliver Nigerians from a system that recycles old politicians with new tricks, politicians who move shamelessly from one party to another in pursuit of power? Once again, Nigerians are being asked to choose among familiar names: President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, Atiku Abubakar, Peter Obi, and Omoyele Sowore. Each champions a movement and claims the capacity to navigate Nigeria out of crisis.

But can their personalities and records truly justify that trust? Can Nigerians finally get it right for once? Will our votes truly matter? And will the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) conduct a free and fair election?

One of the most persistent criticisms of Nigeria’s political system is the recycling of the same political figures. Politicians frequently defect from one party to another, not based on ideology or policy differences, but in pursuit of personal survival and proximity to power. Whenever a party produces the president, defections to the ruling party follow almost immediately, further blurring the line between opposition and government.

This culture has reinforced public cynicism. To many Nigerians, the APC and PDP are less rivals than two sides of the same coin, populated by “old dogs with new tricks,” offering fresh slogans while delivering familiar disappointments.

As Nigeria inches closer to the 2027 general election, a familiar national anxiety is resurfacing, shaped by decades of dashed hopes, recycled political actors, and a deepening crisis of trust in democratic institutions. For many Nigerians, the question is no longer merely who will win the next presidential election, but whether it is still possible to hold an election that is truly free, fair, and capable of producing credible leadership at Aso Rock.

Since the return to civilian rule in 1999, Nigeria’s presidential politics has largely revolved around a closed circuit of political elites. Power has alternated primarily between two dominant parties, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and the All Progressives Congress (APC). Yet, for many citizens, the differences between them appear increasingly cosmetic. Defections have become routine, ideological consistency rare, and governance outcomes disappointingly similar regardless of which party occupies the presidency.

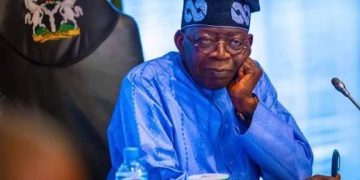

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu is widely expected to seek re-election in 2027. His supporters argue that structural reforms, particularly the removal of fuel subsidies and the unification of exchange rates were painful but necessary foundations for long-term economic recovery. Critics, however, counter that these policies have worsened the cost-of-living crisis, pushed millions further into poverty, and failed to deliver immediate relief or visible improvements in security.

If granted another four years, the question is this what would Tinubu do differently to justify renewed public trust?

For his presidency to leave a positive mark on the lives of ordinary Nigerians, a second term would require more than policy explanations. It would demand tangible improvements in electricity supply, job creation, food affordability, security, and institutional accountability. Without clear, people-centered outcomes, the argument for continuity risks sounding like an appeal for patience without guarantees.

The 2023 election disrupted Nigeria’s traditional two-party dominance, largely due to the emergence of Peter Obi under the Labour Party. Obi’s campaign resonated with millions, especially youths, who saw in him a break from elite entitlement and fiscal recklessness. His record as former governor of Anambra State, marked by prudence and investment in education and healthcare, continues to speak in his favour.

Yet governing at the federal level is vastly more complex than running a state. The presidency requires managing entrenched interests, navigating security challenges across multiple regions, and working with a National Assembly often driven by patronage politics. The central question remains: can Obi replicate his state-level discipline and reformist ethos at the national scale, or would the federal system overwhelm even the most well-intentioned leader?

Obi has argued that 48 months is sufficient for a focused leader to make a significant impact. Whether Nigerians will again rally behind that belief, or demand clearer coalition-building and broader national outreach, will be decisive.

Omoyele Sowore represents a different political proposition altogether. Unlike his contemporaries, he has never held public office. His reputation is rooted in activism, journalism, and relentless advocacy for the oppressed. To many young Nigerians, he embodies courage, consistency, and an uncompromising rejection of a system they view as fundamentally broken.

However, translating protest politics into governance is a formidable challenge. Running a country of over 200 million people requires institutional experience, political negotiation, and administrative capacity. The unresolved question is whether Sowore could become the first Nigerian leader to turn radical promises into practical governance, or whether the system he opposes would resist him at every turn.

As 2027 approaches, political realignments are already underway. Discussions of a broad opposition coalition involving figures such as Atiku Abubakar, Peter Obi, and other power brokers, possibly under platforms like the African Democratic Congress (ADC) have intensified. Internal dissatisfaction within the ruling APC has also fueled speculation about fractures that opposition forces could exploit.

While coalitions may improve electoral competitiveness, they do not automatically guarantee credibility or ideological clarity. Nigerians are increasingly wary of alliances formed solely to win power rather than to govern differently.

At the heart of Nigeria’s democratic dilemma lies the issue of electoral integrity. Can the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) deliver an election whose outcome truly reflects the will of the people? The answer to this question may determine whether citizens remain engaged or retreat further into apathy and despair.

For a population battered by inflation, a weakening naira, unemployment, and worsening insecurity, the stakes could not be higher. The 2027 election is not merely about political victory; it is about national survival, social cohesion, and restoring faith in the idea that leadership can still make a difference.

Nigeria’s current crisis is widely described as a failure of leadership, characterized by corruption, lack of empathy, and governance that prioritizes elite interests over public welfare. Yet the growing political awareness among youths, increased civic engagement, and persistent public debate suggest that the desire for change remains alive.

Whether that desire can overcome entrenched power structures, electoral manipulation, and elite consensus remains uncertain. But one truth is clear: Nigerians are exhausted, yet not indifferent. The outcome of 2027 will not only determine who occupies Aso Rock it will signal whether Nigeria’s democracy can still renew itself, or whether the cycle of recycled leadership will continue unbroken.

The burden of choice, once again, rests with the people, and with the institutions meant to protect their voice.

Daniel Nduka Okonkwo is a seasoned writer, human rights advocate, and public affairs analyst renowned for his incisive commentary on governance, justice, and social equity. Through Profiles International Human Rights Advocate, he champions accountability, transparency, and institutional reform in Nigeria and beyond. With over 1,000 published articles indexed on Google, his work has appeared on Sahara Reporters and other leading international media platforms.

He is also an accomplished transcriptionist, petition writer, ghostwriter, and freelance journalist, widely recognized for his precision, persuasive communication, and unwavering commitment to human rights.

📧 Contact: dan.okonkwo.73@gmail.com