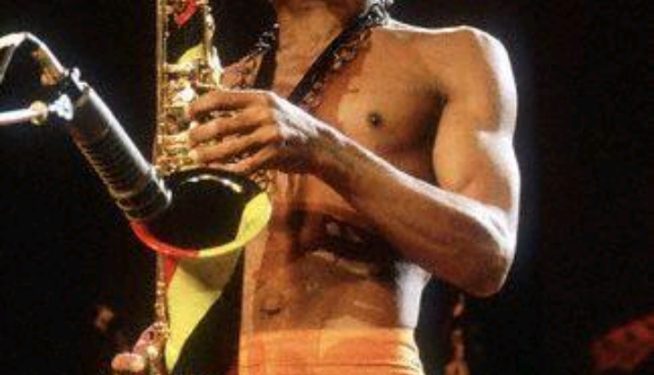

Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì was not only visible in music but also deeply embedded in Nigeria’s democratic struggle. He was a master of his time who fought relentlessly for the betterment of Nigeria. Unlike many modern music superstars who are afraid to speak out or challenge the system, Fela consistently confronted power. He openly criticized Nigerian governments and military dictatorships, attacked corruption, exposed state brutality, and condemned African elites for betraying their people and culture.

His activism was not symbolic; it was lived. Fela endured over 200 arrests, repeated beatings, imprisonment, and the destruction of his Kalakuta Republic. Most tragically, a 1977 military raid led to the fatal injury of his mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, a renowned women’s rights activist whose influence shaped Fela’s political consciousness from birth.

The awards, global recognition, corporate endorsements, and international platforms enjoyed by contemporary Nigerian artists, including Grammy recognition, exist largely because Afrobeat and its descendants broke global barriers. That path was forged by Fela at immense personal cost. His music has endured for over six decades, remaining relevant across generations, cultures, and political eras, an enduring exemplification of its depth and purpose.

Comparing artists across generations is a delicate exercise, particularly when one figure is a cultural revolutionary and the other a global pop icon. Recent debates placing Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì alongside Wizkid reflect a broader misunderstanding of what artistic comparison truly entails and where such comparisons should reasonably end.

From a purely musical standpoint, comparisons often focus on technical elements: vocal timbre, instrumental mastery, stylistic approach, emotional delivery, lyrical structure, or production choices. These criteria can help illuminate differences or similarities in artistic output without descending into fan-driven subjectivity. However, when Fela Kútì enters the conversation, the scope expands beyond music alone.

Fela was not merely a musician; he was the architect of Afrobeat and a pioneer of musical activism. In the late 1960s, he created Afrobeat by blending traditional Yoruba rhythms with jazz, funk, and highlife, transforming sound into a weapon of political resistance. Afrobeat was never just entertainment it was confrontation, ideology, and cultural defiance. That singular decision to weaponize music laid the foundation upon which today’s Afrobeats industry stands.

Even imprisonment did not silence him. In 1984, Fela was jailed by the military government led by Muhammadu Buhari, only to return to music and resistance upon his release. Until he died in 1997, Fela remained uncompromising, using his art to demand accountability, African unity, and liberation from colonial and neo-colonial structures.

By contrast, Wizkid represents a different era and a different relationship between music and power. As one of Nigeria’s most successful global exports, Wizkid has mastered contemporary Afrobeats commercially driven, sonically polished, and internationally marketable. His achievements are undeniable. However, he has largely avoided direct political engagement. Even amid severe economic hardship, insecurity, and systemic failure in Nigeria, he prefers silence. This reluctance, especially at a time when Nigerians endure deteriorating conditions and hardship, has been interpreted by many as indifference, even selfishness, though some fans choose not to acknowledge it.

This silence has drawn criticism, particularly because Nigerians many of whom bear the weight of the country’s challenges, are the same people who fund the lifestyles and global success of these artists by streaming their music and attending their shows around the world. The reluctance of Nigeria’s biggest music stars to openly criticize governance, often due to fear of repercussions, stands in stark contrast to Fela’s fearless defiance.

Recent controversies involving Seun Kuti, Fela’s son, a prominent Afrobeat musician in his own right have further fueled the debate. During an Instagram Live session, Seun pushed back against Wizkid fans who demanded that he drop his longtime nickname, “Big Bird,” claiming Wizkid, popularly called the “Biggest Bird,” now owned the title. Seun rejected the demand, stating that he had used the name long before Wizkid and accusing fans of deliberately dragging his late father into unnecessary online rivalries. “Wizkid stole my name. Tell your fave to be original,” Seun said. “Why are you telling me to change it? Sorry, I can’t change it. This name has been here since. I am the first to come up with it.”

The situation escalated after reports circulated online alleging that Wizkid claimed to be “bigger than Fela” during the exchange an assertion that sparked widespread backlash. For many, the issue was not popularity or streaming numbers, but historical weight and cultural impact.

Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì was not chasing charts or global validation. He was confronting systems, dictatorships, and injustice at a time when doing so carried real and immediate danger. His Afrobeat was inseparable from activism; it inspired generations of African musicians and activists alike, shaping global perceptions of African music and resistance.

Comparing Wizkid to Fela without acknowledging this fundamental difference is intellectually dishonest. Wizkid may be a global superstar of modern Afrobeats, but Fela remains the godfather of Afrobeat the creator, the founder, the blueprint. One represents commercial success within an existing system; the other dedicated his life to challenging and dismantling oppressive systems through music.

These are not merely different artists. They are products of different philosophies, risks, and responsibilities. And while both occupy important places in African music history, Fela’s legacies operate on fundamentally different planes.

Daniel Nduka Okonkwo is a seasoned writer, human rights advocate, and public affairs analyst renowned for his incisive commentary on governance, justice, and social equity. Through Profiles International Human Rights Advocate, he champions accountability, transparency, and institutional reform in Nigeria and beyond. With over 1,000 published articles indexed on Google, his work has appeared on Sahara Reporters and other leading international media platforms.

He is also an accomplished transcriptionist, petition writer, ghostwriter, and freelance journalist, widely recognized for his precision, persuasive communication, and unwavering commitment to human rights.

📧 Contact: dan.okonkwo.73@gmail.com