The question is not whether democracy should be funded, it must. The question is whether Nigeria is funding reform or financing repetition.

Nigeria is often called a “developing country,” but development is not a slogan; it is a trajectory. Nations escape the “third-world” trap when leaders deliberately build institutions that outlive personalities. Elections are the heart of that project. If they remain compromised, no budget, no matter how large, can redeem them.

Why do doubts persist despite escalating budgets? Because Nigeria’s election problem is not merely financial; it is structural.

High levels of corruption are rooted in a complex interplay of weak institutions, high poverty, opaque political financing, and a chronic lack of accountability. These conditions create fertile ground for vote-buying, compromised officials, and the capture of electoral processes by moneyed interests. When poverty is severe, a small inducement can sway a desperate voter. When parties are funded through shadowy channels, campaign spending becomes a pipeline for illicit cash. When enforcement is weak, impunity thrives.

In this context, pouring more money into the same system risks recycling corruption at a higher price.

As Nigeria inches toward the 2027 general elections, the country confronts a painful contradiction: unprecedented financial allocations to the electoral umpire amid unprecedented economic hardship for ordinary citizens. Traders cannot afford transport to their shops. Civil servants struggle to get to work. Parents are defaulting on school fees. Tenants face eviction. Even homeowners are barely able to feed their families. Yet, in the middle of this national squeeze, the federal government has proposed ₦1.01 trillion for the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) to conduct the next polls.

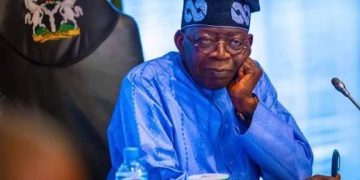

The figure ₦1,013,778,401,602, was included in President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s ₦58.18 trillion 2026 Appropriation Bill presented to the National Assembly. Tagged the “Budget of Consolidation, Renewed Resilience and Shared Prosperity,” it projects ₦34.33 trillion in revenue, ₦58.18 trillion in spending, and ₦15.52 trillion for debt service. Within that vast envelope, INEC’s allocation stands out as one of the largest in its history, reflecting the government’s claim that credible elections require early and adequate funding.

INEC has long argued that logistics, technology, voter education, and nationwide staff deployment demand heavy upfront investment. Indeed, Section 3(3) of the Electoral Act 2022 mandates that election funds be released at least one year before polling to enable proper preparation. In principle, early release should reduce last-minute improvisation and improve integrity.

But in Nigeria’s lived experience, more money has not translated into more trust.

Nigeria’s election budgets have ballooned dramatically over the past decade:

2015: about ₦108.8 billion

2019: ₦143 billion approved by the National Assembly

2023: ₦355 billion approved; ₦313.4 billion released and spent

2025 (INEC’s statutory operations): revised upward to ₦140 billion from ₦40 billion

2027 (proposed): ₦1.01 trillion

INEC’s own technical leadership has reinforced expectations of a very expensive 2027. In October, Prof. Bolade Eyinla, the immediate past Chief Technical Adviser to the INEC Chairman, projected that the commission may need about ₦870 billion (roughly US$600 million) to run the next general election. The government’s proposed figure exceeds even that estimate.

INEC Chairman Prof. Joash Amupitan has again pledged that the commission is ready to organise a process that is “free, transparent and beyond reproach.” Similar assurances were given in 2015, 2019, and 2023. Yet after each cycle, Nigerians are left to reconcile the promises with the discrepancies, logistical failures, disputed tallies, delayed uploads, court battles, and allegations of compromised officials, that follow.

INEC and its defenders often argue that Nigeria’s elections are among the least expensive per voter in comparative terms. Using figures cited by Prof. Eyinla:

Kenya: US$25.9 (2017); US$14.9 (2022)

Ghana: US$13.1 (2016); US$7.7 (2020)

South Africa: US$5.1 (2019); US$7.1 (2024)

DR Congo: US$22; US$14.37 (2023)

Liberia: US$22 (2023)

India: US$8.5 (2019)

On paper, Nigeria compares favorably. In reality, cost efficiency means little without credibility. An election that is cheaper per voter but produces contested outcomes, prolonged litigation, and public disillusionment is far more expensive to a democracy in the long run.

What sharpens the controversy is timing. Nigerians are living through one of the most punishing economic periods in recent history. Transport costs have exploded. Food prices are volatile. Rent is crushing. Public sector wages lag far behind inflation. Against this backdrop, ₦1.01 trillion for elections feels, to many, like a moral and economic provocation.

If the 2027 allocation is to mean anything, three shifts are non-negotiable

Every naira must be tracked, from procurement of technology to recruitment of ad-hoc staff, with real-time public reporting and independent audits.

Institutional accountability: Electoral offences must be prosecuted swiftly and publicly, regardless of political affiliation. Without consequences, money will keep corrupting the process.

Campaign spending limits, donor disclosure, and enforcement must be strengthened so elections are not auctions to the highest bidder.

As 2027 approaches, Nigerians are not asking for cheaper elections. They are demanding honest ones. The tragedy would be to spend ₦1.01 trillion only to be told, once again, to accept outcomes that do not reflect the people’s will. In a country where families are barely surviving, that would not just be wasteful, it would be unforgivable.

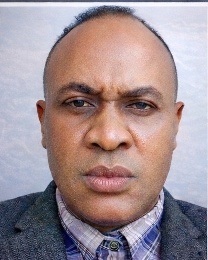

Daniel Nduka Okonkwo is a seasoned writer, human rights advocate, and public affairs analyst known for his incisive commentary on governance, justice, and social equity. Through Profiles International Human Rights Advocate, he champions accountability, transparency, and reform in Nigeria and beyond. With over 1,000 published articles indexed on Google, his work has appeared on Sahara Reporters and other leading media platforms. He is also an accomplished transcriptionist, petition writer, ghostwriter, and freelance journalist, recognized for his precision, persuasive communication, and unwavering commitment to human rights.

📧 Contact: dan.okonkwo.73@gmail.com