Confronting the United States is often likened to an amateur stepping into the ring with a seasoned professional. The imbalance of power is stark, yet history shows that many leaders are encouraged into such confrontations by loud voices on the sidelines, supporters who cheer defiance but disappear when consequences arrive. When defeat becomes unavoidable, these same voices retreat into moral posturing and criticism, unwilling to confront the power they once urged others to challenge.

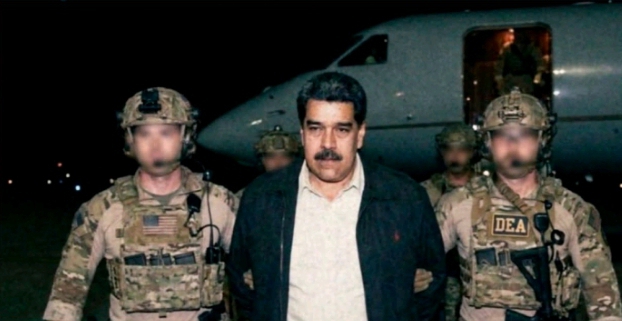

History has repeatedly illustrated this pattern. Venezuela offers a useful illustrative case. Imagine a hypothetical scenario in which the United States launches a decisive, large-scale military operation, captures President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, and flies them out of the country. Such an outcome, while speculative, would starkly demonstrate the futility of confrontation with an overwhelmingly dominant global power. More importantly, it would expose how reckless brinkmanship is often sustained by external encouragement from actors who bear none of the political, economic, or human costs when disaster strikes.

This recurring lesson emphasizes a hard truth of international politics: symbolic defiance may attract applause, but it is strategic realism, not bravado, that ultimately determines a nation’s survival and stability.

For more than two centuries, the United States has played an outsized role in shaping global political outcomes through foreign interventions. Often framed around economic opportunity, the promotion of democracy, the defense of human rights, regional stability, and the containment of perceived threats, U.S. involvement abroad has been extensive, and, at times, deeply controversial.

Scholarly and historical records indicate that the United States has undertaken nearly 400 military interventions between 1776 and 2026, with approximately half occurring after 1950 and more than a quarter taking place in the post–Cold War era. These actions have ranged from overt military invasions to covert intelligence operations designed to influence, destabilize, or replace foreign governments.

Throughout the Cold War and beyond, U.S. foreign policy frequently prioritized strategic and economic interests over democratic outcomes. Notable examples include:

Iran (1953): A CIA- and MI6-backed coup overthrew the democratically elected Prime Minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, after he moved to nationalize Iran’s oil industry. Power was consolidated under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a pro-Western monarch. This intervention contributed to long-term instability and ultimately to the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Guatemala (1954): The United States supported a coup that removed President Jacobo Árbenz after his land reforms threatened U.S. corporate interests. His ouster ushered in decades of military rule and civil conflict.

Cuba (1961): The Bay of Pigs invasion, a failed CIA-backed operation, sought to overthrow Fidel Castro’s communist government and remains one of the most infamous miscalculations in U.S. foreign policy.

Chile (1973): Following the election of socialist President Salvador Allende, U.S.-backed destabilization efforts contributed to a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet, resulting in a brutal dictatorship that lasted until 1990.

Panama (1989): President George H. W. Bush ordered the invasion of Panama (Operation Just Cause), removing General Manuel Noriega, a former U.S. ally, and extraditing him to the United States on drug trafficking charges.

Iraq (2003): The U.S.-led invasion toppled Saddam Hussein, justified by allegations of weapons of mass destruction and promises of democratic transformation. The aftermath, however, was marked by prolonged insurgency, sectarian violence, and regional instability.

Earlier interventions, particularly the “Banana Wars” in Central America and the Caribbean, similarly reflected efforts to protect U.S. economic and strategic interests by installing compliant regimes in countries such as Honduras, Nicaragua, and Haiti.

In the 21st century, U.S. interventions in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) were framed within the broader “War on Terror.” While these operations succeeded in removing the Taliban from power and overthrowing Saddam Hussein’s government, the long-term outcomes raised serious questions about nation-building, civilian harm, and respect for national sovereignty.

Against this historical backdrop, recent claims circulating globally have sparked debate over U.S. interventionism. According to statements by U.S. President Donald Trump, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife were captured and flown out of the country during what was described as a large-scale U.S. military operation.

Trump said that elite U.S. forces carried out the operation and that the United States would temporarily “run” Venezuela. He further said that Maduro headed a vast criminal network involving drug trafficking and cooperation with groups designated by the United States as terrorist organizations, accusations the Venezuelan government has consistently denied.

These claims have international concern and condemnation, raising serious questions about their verification, legality, and implications under international law.

China officially condemned what it described as U.S. military action against Venezuela, calling for respect for national sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs.

In Nigeria, human rights activist Omoyele Sowore sharply criticized both the United States and the United Nations, accusing Washington of pursuing an illegal regime-change agenda and describing the alleged seizure of Maduro as a “kidnapping.”

“The time has come to confront an uncomfortable truth,” Sowore said, arguing that the United Nations has become “impotent, compromised, and largely irrelevant” in the face of unilateral military actions by powerful states.

Similarly, a Nigeria-based Venezuela Solidarity Group condemned the reported operation and demanded clarification regarding the whereabouts and status of Venezuela’s president.

The unfolding controversy has renewed attention on the laws of war, which govern both the justification for initiating armed conflict (jus ad bellum) and the conduct of hostilities (jus in bello). These legal frameworks emphasize state sovereignty, proportionality, military necessity, and the protection of civilians, while restricting actions such as unlawful occupation, extrajudicial detention, and regime change imposed by force.

Unilateral military actions, particularly those aimed at forcibly removing a sitting head of state, raise profound concerns under the UN Charter and established principles of international law.

U.S. foreign policy counters that regimes accused of terrorism, large-scale drug trafficking, and systematic human rights abuses should expect international consequences. Some argue that selective enforcement, the absence of multilateral authorization, and historical precedents of destabilization undermine claims of moral authority.

The proponents of U.S. hard power, said that the United States has played a decisive role in confronting and destabilizing what it perceives as criminal or terrorist-driven administrations across the globe. Pointing to recent security developments, including reported airstrikes on multiple terrorist hideouts in Sokoto, Nigeria, on December 25, 2025, as evidence of Washington’s willingness to act decisively against transnational terror networks, particularly when local and international security interests converge.

From this perspective, certain states and non-state actors are seen as operating beyond the bounds of negotiation. As the argument goes, there are countries and organizations one cannot confront without consequence: if they come after you, you lose; if you go after them, you still lose. In this worldview, deterrence is rooted not in diplomacy but in overwhelming force.

Consistent with long-standing doctrine, the United States maintains that it does not negotiate with terrorists, viewing compromise as an incentive for further violence rather than a path to peace.

What remains indisputable is that U.S. involvement in regime change is not new; it is deeply embedded in modern history. Whether such actions promote long-term stability or merely perpetuate cycles of conflict remains a subject of intense global debate.

As the controversy over Venezuela continues to unfold, whether based on verified events or contested claims, it serves as a stark reminder of an unresolved dilemma in international affairs: for governments accused of repression and criminal governance, confrontation with global power structures remains a persistent and perilous possibility, while for the international community, the challenge of upholding law over force remains as urgent, and elusive, as ever.

Daniel Nduka Okonkwo is a seasoned writer, human rights advocate, and public affairs analyst known for his incisive commentary on governance, justice, and social equity. Through Profiles International Human Rights Advocate, he champions accountability, transparency, and reform in Nigeria and beyond. With over 1,000 published articles indexed on Google, his work has appeared on Sahara Reporters and other leading media platforms. He is also an accomplished transcriptionist, petition writer, ghostwriter, and freelance journalist, recognized for his precision, persuasive communication, and unwavering commitment to human rights.

📧 Contact: dan.okonkwo.73@gmail.com