Mali reciprocated in equal measure, and the United States removed its name from the list.

Mali, despite its rich gold reserves and fertile agricultural base, remains among the world’s least developed nations. Political instability, climate pressures, rapid population growth, and heavy dependence on foreign aid have continued to constrain its progress. Persistent poverty, conflict, and weak governance keep the country firmly within the low-income category.

Yet, against the odds and with little conventional leverage, Mali managed to persuade the United States to strike its name from a discriminatory visa-bond list.

In late 2025, Mali was reportedly added to the same U.S. visa-bond pilot program now affecting Nigerians. Rather than limit its response to diplomatic protests, Bamako acted decisively. The Malian government announced reciprocal measures, imposing a comparable visa bond requirement on U.S. citizens seeking entry into Mali. The message was unmistakable: Malian citizens would not be singled out without consequence.

The result was swift. Faced with diplomatic pressure and the long-standing international principle of reciprocity, one the United States itself frequently invokes, Washington reversed course. Mali was removed from the visa-bond list before the policy could be fully implemented.

It was a rare and telling example of an African nation successfully pushing back against a discriminatory immigration measure.

Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country, a major U.S. trading partner, and a strategic actor in West Africa. Yet on issues that directly burden its citizens, students, entrepreneurs, professionals, and families, the Nigerian state often appears hesitant, reactive, or muted. Diplomacy is not merely about courtesy; it is about leverage, reciprocity, and the protection of citizens’ dignity. On this issue, the government should be doing everything possible to remove Nigeria’s name from a list that amounts to a national embarrassment.

Protecting citizens abroad is not a favor; it is a constitutional responsibility. Silence risks normalizing a dangerous precedent, one in which Nigerians are treated as high-risk travelers by default. Leadership demands more than campaigning for re-election; it requires standing firm when national dignity and citizens’ rights are at stake.

The Federal Government of Nigeria has options. It can seek exemptions, negotiate revised thresholds, present compliance reforms, or if necessary apply reciprocal measures, as Mali did. What it must not do is nothing.

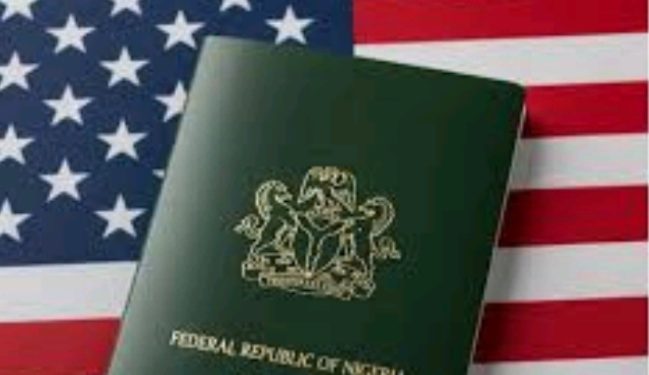

A new United States visa-bond policy scheduled to take effect on January 21, 2026, raises serious questions about fairness, proportionality, and respect for Nigerian citizens. Under this pilot program, some Nigerian applicants for U.S. tourist and business visas (B1/B2) may be required to deposit a refundable bond of up to $15,000, with other possible tiers of $5,000 or $10,000, as a guarantee that they will depart the United States before their authorized stay expires.

At current exchange realities, the $15,000 bond alone translates to approximately ₦22.5 million. When combined with tuition deposits (for students), visa fees, flight tickets, insurance, accommodation, and logistics, the total financial exposure for a Nigerian traveler or student can exceed ₦70 million, depending on the purpose and duration of travel.

This is an extraordinary burden in a country already grappling with inflation, currency depreciation, and declining household incomes.

The stated justification for the bond is Nigeria’s visa overstay rate. The bond functions as a security deposit: it is returned only if the traveler exits the United States on time, often through designated ports of departure to confirm compliance. If the traveler overstays, the bond is forfeited.

In effect, this policy presumes risk before conduct, imposing collective punishment on millions of law-abiding Nigerians because of the actions of a few.

What makes this moment particularly instructive is Mali’s response.

This raises a fundamental question: if Mali can act, why can’t Nigeria?

No serious observer argues that immigration compliance should be ignored. Overstays are a legitimate concern for any sovereign state. However, enforcement measures must be proportionate, non-discriminatory, and negotiated, not imposed in a manner that effectively prices an entire nationality out of global mobility. A refundable bond of $15,000 does not merely deter overstays; it excludes the middle class and criminalizes aspiration.

If the Nigerian government is unsure where to begin, the blueprint already exists, in Bamako.

Mali demonstrated that resistance is possible. Nigeria should take the hint and act.

Daniel Nduka Okonkwo is a seasoned writer, human rights advocate, and public affairs analyst renowned for his incisive commentary on governance, justice, and social equity. Through Profiles International Human Rights Advocate, he champions accountability, transparency, and institutional reform in Nigeria and beyond. With over 1,000 published articles indexed on Google, his work has appeared on Sahara Reporters and other leading international media platforms.

He is also an accomplished transcriptionist, petition writer, ghostwriter, and freelance journalist, widely recognized for his precision, persuasive communication, and unwavering commitment to human rights.

📧 Contact: dan.okonkwo.73@gmail.com